What bullshit essentially misrepresents is neither the state of affairs to which it refers nor the beliefs of the speaker concerning that state of affairs. Those are what lies misrepresent, by virtue of being false. Since bullshit need not be false, it differs from lies in its misrepresentational intent. The bullshitter may not deceive us, or even intend to do so, either about the facts or about what he takes the facts to be. What he does necessarily attempt to deceive us about is his enterprise. His only indispensably distinctive characteristic is that in a certain way he misrepresents what he is up to.

This is the crux of the distinction between him and the liar. Both he and the liar represent themselves falsely as endeavoring to communicate the truth. The success of each depends upon deceiving us about that. But the fact about himself that the liar hides is that he is attempting to lead us away from a correct apprehension of reality; we are not to know that he wants us to believe something he supposes to be false. The fact about himself that the bullshitter hides, on the other hand, is that the truth-values of his statements are of no central interest to him; what we are not to understand is that his intention is neither to report the truth nor to conceal it. This does not mean that his speech is anarchically impulsive, but that the motive guiding and controlling it is unconcerned with how the things about which he speaks truly are.

Friday, August 29, 2008

in our thoughts lately

Thursday, August 28, 2008

Tuesday, August 26, 2008

Bloggrrrrrrrrr

big girl's blouse

(thinking of writing apologetic e-mail re still unfinished review, along the lines of 'sorry to be such a big girl's blouse', I wonder whether, as an American, I have really mastered the idiom, turn to our dear friends at Google and find....)

[Q] From Colin Alexander, New Zealand: “Big girl’s blouse. How did this extraordinary pejorative come about? It is usually applied to males and seems to mean a milquetoast, but how?”

[A] For those in other parts of the English-speaking world who have never heard of this astonishing idiom, let me explain that it is heard now quite widely in Britain (and elsewhere, too, it seems), though it originated in the North of England.

I’ve been vaguely dreading somebody asking this question, because it is one of a set of Northern idioms that are quite impenetrable in their origins. Others are the exclamation of surprise, “well, I’ll go to the foot of our stairs!” and the dismissive “all mouth and trousers”.

People do indeed use it to mean an ineffectual or effeminate male, a weakling, though it is often used in a bantering or teasing way rather than as an out-and-out insult (“You can’t drink Coke in a pub, you big girl’s blouse!”; “Blokes who don’t take on dares are big girl’s blouses”). The American milquetoast isn’t quite equivalent (since it has a greater emphasis on meekness rather than on an unmanly nature), but it’s close.

the rest here

(the consensus seems to be that it is some kind of put-down delivered to men, but I first came across it when my friend Sue McCafferty, who had grown up in the Lake District, said, 'Oooooooh [oo as in cool] babes, sorry to be such a big girl's blouse', and I said '¿Qué?')

how did we get here from there?

Although Albert Camus died before baby boomers took charge of the world and placed their redoubtable imprimatur on the political scene, he foreshadowed their eventual devolution in this prescient statement: "Conformity is one of the nihilistic temptations of rebellion which dominate a large part of our intellectual history. It demonstrates how the rebel who takes to action is tempted to succumb, if he forgets his origins, to the most absolute conformity. And so explains the twentieth century."

Camus was right, of course. As a baby boomer, it doesn't make me happy to say this; however, how else does one explain the "absolute conformity" (not to mention hypocrisy) of my once-rebellious generation? How else does one explain the disgraceful situation in which our country now finds itself?

We can't blame Nixon any more, although it would be fun to still kick him around. No, we have to look inward. We're the ones who created this mess. We're the ones who abrogated our political idealism and slowly but surely conformed to establishment power and corporate materialism. And we're the ones who allowed George W. Bush, a baby boomer of the worst sort, to slime his way into the presidency and bankrupt the country both economically and morally.

John F. Miglio in Counterpunch, courtesy Wood's Lot, the rest here

Monday, August 25, 2008

Softer World 2

Sunday, August 24, 2008

don't look now

XIII. The work is the death mask of its conception.

Walter Benjamin on writing, from Marginal Revolutionsofter world interview

post-Socratics

A few days ago Wyatt Mason posted a letter from Malcolm Lowry to Andre Barzun objecting to what he saw as an unfair review. This was the third time Mason had nailed his colours to the mast, coming out in favour of authors' responding publicly to their critics; the topic was first raised back in May, when Mason reported on a public dialogue at Harvard between James Wood and Jonathan Franzen. When the floor was opened to questions, Mason weighed in.

In Franzen's shoes, I would have been inclined to wonder whether lack of enterprise on the part of writers of fiction was really the only, or even more probable, explanation for the data. The editors of the NYRB may receive no letters from writers of fiction - or, of course, they may receive them and choose not to publish them. Or, of course, writers of fiction may notice that we never see letters from writers of fiction in the letters pages, assume that this represents editorial policy of the NYRB, and refrain from writing in on the assumption that they would not get published. In the absence of further data, we can only surmise.I asked if I might follow up. “Why then,” I asked, “is it that the back pages of the New York Review of Books are filled with non-fiction writers responding to the indignities heaped upon them by critics who [they believe to have] missed their argument, but fiction writers don’t feel the same liberty to respond to their critics and say: ‘You’ve missed it.’ Is it beneath the dignity of art to respond to your accuser?”

“You can actually dispute facts,” Franzen said, “but you can’t dispute taste. That’s the sorry condition of the artist. There’s no proving it.”

Franzen, anyway, not only failed to make this point but let the side down even further by a variation of 'Well, it's all subjective, innit?' Mason might helpfully have suggested that Mr Franzen go away and read A C Danto's The Transfiguration of the Commonplace; sadly, he had more important fish to fry. He cites all the things Franzen has done to participate in critical debate, then goes on

Taking on faith—for a few more lines—that there is indeed an adequate supply of rigorous literary criticism of imaginative works of prose, I would dismiss as poppycock that “there’s no one out there responding intelligently.” Rather, the problem, and I do see it as one, is that too few serious readers and writers who are upset by the supposed absence of criticism are actually responding intelligently to—much less taking the time to notice—the very good criticism we have in abundance.

I do not mean that there exists a disappointing number of responses to criticism. The web is now fortunately full of blogs that take note—often very keenly—of such views and reviews. But a 50- or even 500-word post, however intelligent, in response to a 5,000-word essay (in response to an 85,000 word novel) can only be, by nature and degree, an inadequate response.

What can be done? To begin, if a novelist should receive a dumb review of his book, my belief is that he should feel not merely at liberty but honor-bound to respond intelligently, in public, in writing.... For those writers who do not feel that their special islands are similarly safe from tsunamis of critical stupidity; who themselves do not feel Nabakovianly above it all; who feel the culture is drowning what is better in waves of what is worse; who feel hurt and assailed and misread and misunderstood, who feel that a critic has failed to appreciate, failed to feel the full force of, the book the fiction writer believes he has written—I argue that he must engage with these inferior engagements....

“You can’t dispute taste,” said Franzen, and I would not ask him to. [He might also find Fowler's Kinds of Literature and Wayne Booth's Rhetoric of Irony helpful; these cover most of the kinds of mistake one sees in reviews.] I would ask, however, that he and his peers—when confronted with the insensate maunderings of someone they deem a dim bulb in the critical stoplight—respond nonetheless. If a review under-appreciates not merely one’s own book but that of a peer, respond. Not with hurt feelings but with strong arguments that showcase the rigors of construction, of patterning, of metaphor, of the myriad deliberate choices serious writers deploy to the end of making not tasteful works but artful ones. The Corrections, for example, was not a work of taste; rather one of Art. As such, in an era in which there is less shelf space for seriousness, fiction writers must take the responsibility of reprimanding their critics for their stupidity more seriously, more regularly.

here

I was rather surprised to see this professed passion for public debate on a blog which did not take comments. Insensate maunderings seems a bit harsh, but to the untutored eye there is a certain lack of consistency. The untutored eye was even more baffled to find Mason taking up the theme not once but twice, first writing of a letter from Philip Roth to Diana Trilling, then of one from Lowry to Barzun:

Though I continue to believe that what literary conversation we do have about fiction would be fortified were more creative writers to thoughtfully return critical fire now and again, I concede that the likelihood of such a craze sweeping through our novelistic ranks is low indeed. So low, in fact, that very richest example I’ve been able to find of a novelist adequately replying to a critic was written but, alas, never sent.(roth)

Lowry’s own reply only further confirms my sense that one can do better, even in this uncivil time, when receiving criticism however harsh (not to say when meting it out) than the hurling of insults. It is perhaps useful to be reminded that when people exchange words about art, we are witnesses not, as the lately popular coinage has it, to a “Literary Smackdown!” but to civilization—a term forever in need of definition.Comments were still off, so I decided to go straight to the horse's mouth and contact Mason by e-mail.

(lowry)

HD:

You've said on your blog that a writer who thinks he got a dumb review should feel not merely at liberty but honor-bound to reply intelligently, in public, to the critic. I'm wondering what exactly you think writers should do who disagree with your reviews. "Ought implies can," says Kant; your blog doesn't accept comments.Mason replied: he thought writers should send a letter to the editor. It was Harper's policy not to allow comments on blogs, but he didn't disagree with this: he signed his name to his posts, so it was reasonable to expect commenters to do the same. A writer can either send an e-mail to Harper's Replies, who will decide if it's worth publishing, or they can write to WM's e-mail address, in which case he replies privately.

Well, when people exchange words about art we witness civilization. How much better if the public could witness civilization in the form of an exchange of words about art between the acclaimed novelist and Guggenheim Fellow, Helen DeWitt, and the acclaimed critic, Wyatt Mason! Especially since DeWitt is, in her own opinion, so much better equipped for the debate than the hapless (though admittedly acclaimed) Mr Franzen!

I write:

I'm not sure I follow this - it may be that we have different understandings of what's meant by a public response. Sending a letter to an editor which is certain not to be published doesn't strike me as a public response. Sending a private e-mail to the reviewer is, of course, a private response. Leaving a comment on a blog is a public response, whether or not it is anonymous; it's hard to imagine that a writer who wanted to take issue with a reviewer would conceal his/her identity. It is, of course, perfectly possible to exclude anonymous comments if one wishes to do so.

How do you feel about letting me publish your e-mail on my blog, which does accept comments? It seems to me that some sort of public discussion would be more interesting than thrashing out personal points of difference. My understanding, from your various posts, was that you thought public debate on matters of criticism of some importance.

Well, um, hm. WM's position is, in a nutshell, that an author is honor-bound to offer a magazine the chance to decide whether his views are worth publishing, but the magazine is not honor-bound to make them public, nor is a critic honor-bound to make public letters (like those of Roth and Lowry) which are addressed to him. Nor is the writer who addresses him personally entitled to share the exchange with the public: Mason's responses are made in the context of a private correspondence. They are not public, they're private, and must remain so. So he did not want his e-mail published on the blog, because it was private.

Just to be clear, Mason seems to draw a distinction between the sort of discussion we had been having and a response to a review. The letters he quoted were written by authors about books they felt had been unfairly reviewed; he thought they would have been published if sent to the editor, and that was the forum where such responses should appear. My e-mail, obviously, doesn't fall in that category. It doesn't count as someone in the novelistic ranks returning critical fire, because it's not a response to a review, either of me or anyone else; it's just someone in the novelistic ranks taking issue with Mason's assessment of the opportunities for those in the novelistic ranks to return critical fire, if he and those like him fail to provide them. So we weren't actually exchanging words about art, we were just in talks about talks. And he never said that when we witness talks about talks about art we witness civilization. He never said that when we witness talks about talks about talks about art we witness civilization.

I think most writers don't engage much with critics because they suspect this kind of thing is on the cards.

Anyway, as always, the moral of the story is that I would have been happier as a statistician.

You'll remember that WM thought a letter to the editor was the correct way to advance critical debate. You'll also remember that he thought blogs weren't up to the job, because a 50- or 500-word post is an inadequate response to a 5000-word review. So I decide to see whether there is any evidence that 'Letters to the Editor' is a plausible forum for the sort of letter written by Roth and Lowry. Roth wrote a 2209-word letter that he didn't send. Lowry sent a letter that was 2405 words long. Might these have reached the public if sent to an editor?

I don't have an online sub to Harper's, so I can't do word counts on their letters. I turn instead to the NYRB (you'll remember that WM was surprised that its back pages had no letters from writers of fiction). In the 20 issues published in the last year, the NYRB published 73 letters to the editor (not including replies and letters by the editors); 62 were under 500 words long. The longest was 1100. The following little table is horrible, but shows the distribution:

(No, since you ask, this was not a sensible use of time.)

(No, since you ask, this was not a sensible use of time.)The longest letters tend, in fact, to be responses not to reviews but to political events: an open letter to the Attorney General, an open letter to Bush, an open letter on events in Tibet. A couple of longish letters (upper 300s) were tributes to the dead (Walcott on Hardwick, Epstein on Mailer).

This actually strikes me as a perfectly reasonable allocation of space in the NYRB. If an open letter with distinguished signatories can influence US policy in the Middle East for the better, it's not easy to see why a novelist's response to an ill-judged review should take precedence. Still, that's not to say that public debate on fiction couldn't be a good thing; the question is, is this a plausible choice of venue? Both Lowry's letter and Roth's were more than twice as long as the longest letter published in the NYRB in a year - and that letter was itself an outlier. (After the 1100-word letter, the next longest was 895 words long.) If one genuinely wants to see this sort of letter in the public domain, and one is unhappy with the standard of debate currently on offer in the blogosphere, one needs to push for some other space where such letters can be seen.

(The LRB, since you ask, seems to publish more letters per issue, but the distribution in length is not strikingly different from that of the NYRB.)

Anyhoo. Moving right along.

In The Transfiguration of the Commonplace A C Danto raises the question, how can physically indistinguishable objects be different works of art? How can it be that physically indistinguishable objects can fall in different categories, one a work of art, one not? In Borges' story The Quixote of Pierre Menard, Borges imagines a text written by a 19th-century Frenchman which is identical to that of the Quixote of Cervantes; while the two are indistinguishable, they have different literary properties. (Cervantes wrote in the Spanish of his day, Menard achieved dazzling verisimilitude and so forth.) Duchamp selected a urinal and christened it Fountain; the object continued to be white, shiny, made of porcelain, like its humbler brothers, but it also possessed attributes which were inapplicable to them (impertinent, witty, iconoclastic and so on). And yet, while some artistic properties could be ascribed to it, others would be inappropriate: though Fountain looks exactly like a urinal, to say that it is an accurate representation of a urinal would show a profound misunderstanding of how it functions as a work of art. To describe it as an inaccurate representation of a fountain would, again, show that one had missed the point. And on the other hand again, one can desecrate Fountain in a way that one cannot its siblings, simply by using it for the purpose for which it was originally intended. But someone who does so clearly understands the work; whereas if someone were to wander an art gallery in desperate need of a pee, spot Fountain and think, Oh, GREAT, that's really convenient -- it would be hard to know where to start.

Critics of fiction do often make the various sorts of category mistake sketched out above. So it would have been nice if Franzen had explained that this was why it was more complicated to respond to reviews of fiction than to reviews of non-fiction. It would have been nice if he had pointed out that this would be difficult to achieve in under 500 words. It would be awfully nice if reviewers were allowed to start their reviews with a brief reminder of the wisdom of A C Danto rather than a plot summary. Plato's Socrates goes gallantly into the fray, taking on such fine clever speakers as Gorgias, Protagoras and Thrasymachus; it bothers me that I don't have the intellectual stamina to follow his example, but I don't, or at least not today.

Thursday, August 21, 2008

things change

Nato today said it had received a note from Russia saying it would break off military cooperation with the west's military alliance, in the latest fallout from Russia's short, sharp war with Georgia.

More in the Guardian, here, though you've probably heard this elsewhere. Not sure what to say, except that this seems like the sort of thing that could be the next Sarajevo.

Wednesday, August 20, 2008

regrets, I've had a few

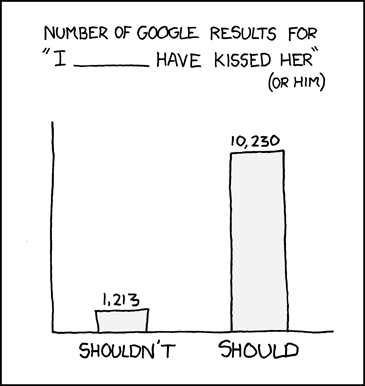

(pop-up: And nothing for I'm glad I saw 'Epic Movie')

AS:

Ich bin ja ein erklärter XKCD-Fan, aber ich finde, dass er in diesem Fall durch die Zusammenfassung der Ergebnisse für him und her eine Chance vertan hat, detaillierteres Wissen über die menschliche Natur herauszufinden. (I'm an avowed xkcd fan, but I think in this case, by amalgamating the results for him and her, he lost a chance to bring to light a more detailed knowledge of human nature.)

AS makes good this important omission, first by running searches in English according to gender:

(pop-up: Tu es oder tu es nicht, du wirst beide bereuen (Sören Kierkegaard) [do it or don't do it, you'll regret both])

(pop-up: Tu es oder tu es nicht, du wirst beide bereuen (Sören Kierkegaard) [do it or don't do it, you'll regret both])and THEN by running searches for Ich hätte ihn/sie (nicht) küssen sollen

(pop-up: Das einzige, was ich bereue, ist das ich nicht jemand anders bin (Woody Allen) [the only think I regret is that I'm not somebody else])

(pop-up: Das einzige, was ich bereue, ist das ich nicht jemand anders bin (Woody Allen) [the only think I regret is that I'm not somebody else])Stefanowitsch has revealed several striking disparities between the anglophone and germanophone worlds of sexual regret - or, at least, disparities between the pools of regretful English and German speakers who feel called upon to share their disappointment on the WWW. (Perhaps English-speaking men are likelier than both English-speaking women and German-speaking men AND women to have no alternative to the kindness of strangers.)

There's a lesson to be learnt.

The lesson, of course, is that Randall Monroe and Antaol Stefanowitsch should collaborate on a T-shirt. Guys. Guys. You know it makes sense.

(Bremer Sprachblog, as so often, brings to mind the possibly apocryphal British headline: Fog in Channel: Continent cut off. In this case, it's the non-German-speaking world that's cut off from this consistently excellent blog; if you know any German at all, check out the rest here.)

Monday, August 18, 2008

on not wanting to talk about it

Sigur Ros

Anyway, came across a post about Sigur Ros on Nico Muhly's site so feel I should post the link for TAR ART RAT, which is here.

(Speaking of links, more people have bought YNH and said the PayPal link is not working.

Sunday, August 17, 2008

brand wars

I wanted to take advantage of the blog form, though, by first introducing readers to Sanghera's style, which I first came across a couple of years ago in the Financial Times. If You Don't Know Me By Now came as a revelation precisely because I had been following Sanghera's column, with its finely tuned comic persona, for months, without (as so often) knowing anything about how it had come into being.

Sanghera took a sabbatical to write his book and is now back, writing for the Times. And today I find that Sanghera has explored an issue raised some time ago on paperpools - that of mad British copycat branding.

Those who've been following the blog may remember the feud between Britannia Pizza and Pasta and Britannia Pizza and Chicken, treasured flyer posted

here. This is, it turns out, no isolated incident. SS:

They say that Britain has become a second-rate nation. They say our greatest brands are controlled by foreigners, that the last half-decent singer-songwriter we produced was Phil Collins, that we're run by a man who can't pronounce “al-Qaeda” properly.

It was hugely encouraging, therefore, to read last week that (i) the Newcott Chef restaurant on the A30 in Devon was being threatened with legal action from Little Chef over its lookalike appearance; and that (ii) the easyCurry Indian restaurant in Northampton was being threatened with legal action from Sir Stelios Haji-Ioannou's easyGroup over its trading name.

the rest here

Thursday, August 14, 2008

lost in transmission

It would be time wasted to debate the disingenuousness of McDowell’s “A note on this book.” But we should still ask: to what end were McDowell’s editorial acrobatics? That is the larger question that the Lofaro edition asks, and it’s a useful question, particularly when not a few writers find themselves in the position of having their novels edited desultorily. Over the years a number of younger writers have confessed to me their frustration at seeing their manuscripts tidied but barely touched before flowing into type (just as any number of readers have asked, “Is anyone editing these things?”). Novels need good editors, editors of taste and vision, to reckon with the imperfections that the novel, in seeking its perfections, generates. The list of books that have been shaped by editors as much as their writers is long and interesting; the invocation of the name Max Perkins serves as flag and totem to the cause.

In the case of Agee’s novel, we readers and amateurs of literature have a rare chance, if it suits us, to see just what an editor does or can do. And specifically, if one were to read the Lofaro Agee first and the McDowell Agee second, a reader would see how well, and not just what, Agee’s editor really did do, after all.

Saturday, August 9, 2008

mechanical man

...

Sue Palmer, author of Toxic Childhood, said: "Robots can't teach. The only effective teaching is by breathing, living teachers who can look a pupil in the eye and respond to them."

on a scheme to use robots to teach phonics to small children, Guardian Education

Wednesday, August 6, 2008

P**P*l

I've tried to write to the most recent buyers but have not worked my way back up through the e-mails. If you tried to buy YNH and failed, please do send me an e-mail and I'll send you the link.

borderliner

Monday, August 4, 2008

Housman thou shouldst be living at this hour

Yes, Odysseus, I watched the progress

of your hunt with some interest.

Fragment of Sophocles' Ajax as translated by John Tipton, quoted at greater length on Wyatt Mason's Sentences

Sunday, August 3, 2008

more R

Thanks to Kabakoff I learn that Deepayan Sarkar's Lattice, Multivariate Data Visualization with R has just been published by Springer. Also great news.

Friday, August 1, 2008

authenticity

Weiner on Mad Men at the NYT